“Pop Art” is a name that reads like a contradiction. Art is often lauded as high-minded and original. Pop is largely disdained as lowbrow and repetitive. But in many ways, the name encapsulates what makes Pop Art design so compelling: it revels in irony and combines what shouldn’t be combined.

Of course, Pop Art design owes its greatness to more than a catchy name. It is an incredibly vibrant, cheeky and diverse style whose appeal has endured for decades, no doubt for its role in wresting fine art from the hands elite to those of the masses. To help you get your own hands-on this aesthetic, we’re going to walk through the roots of Pop Art and the many ways it is still being adapted to this day.

What is Pop Art design?

Pop Art design is a fine art movement that reigned in the mid-1950s and 60s that largely focused on representations of popular, American pop culture iconography. These representations often ranged from literal, such as Roy Lichtenstien’s reproductions of actual comic book panels, to stylized, such as Richard Hamilton’s magazine collages. In contrast to the artwork that highlighted the particular hand of an artist, Pop Art routinely mimicked the impersonal and machine-driven graphics of commercial products.

Like all art, what defines something as Pop Art is not always straightforward—it depends on the particular obsessions and sensibilities that inevitably vary from artist to artist. However, most Pop Art does share a few common elements:

- Subject matter featuring popular Americana such as celebrities, advertisements, shopping catalogs and comic books

- Mass production techniques such as halftone printing

- Excessive repetition

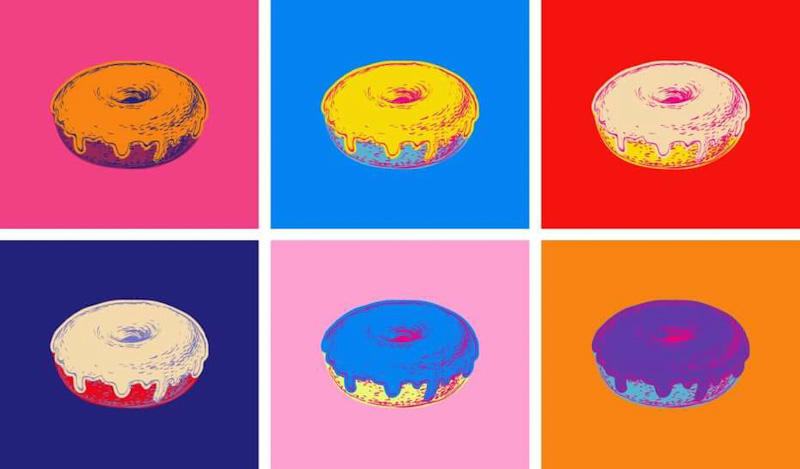

- Image reproductions with substituted colors

While all of this describes the visual features of Pop Art, it fails to truly explain what Pop Art meant to both its artists and its devotees. How did a style that often reproduced the same, over-distributed commercial images manage to have such a lasting impact? In order to understand that, we’ll have to look into the historical context of the time, place and the people involved.

A brief history of Pop Art

The roots of Pop Art

Like so many artistic revolutions, Pop Art was often decried with some variation of This isn’t art! To some extent, these critics had a point: reproductions of commonly available images certainly was not what art had been up until that point.

But at the same time, American art had experienced a relatively recent period of realism, or naturalism. In this movement, artists reclaimed the subject matter of their art from religion or bourgeois portraits to scenes (often gritty) of ordinary people in order to show American life as it truly was. This was contrasted by modernist European movements such as Cubism, Dadaism, and Surrealism, much of which was greeted by Americans in the 1913 Armory Show with consternation and horror—Theodore Roosevelt himself famously declaring of French artist Marcel Duchamp, “He is nuts and his imagination has gone wild!” But all of these movements were vital precursors to Pop Art for challenging how art was supposed to look and what it could be about.

Outside the art world, American life had changed drastically. Industrialization had introduced mass production and crowded urban centers. Later, the end of World War II and the economic boom that followed brought about a mass migration to the suburbs, in search of quiet, residential lives.

At the same time, advertising was ramping up as a defined industry, helped along by new technology such as the radio and the television. Practices that emphasized aspirational imagery, slogans and jingles repeated ad nauseam became commonplace.

Many of the images that ads used during this period—backyard family barbecues, housewives in full hair-and-makeup showing off the latest appliance, enjoying a Coke after some good old American baseball—both reflected and molded the ideal suburban life, what has been branded as “The American Dream.” As such, the values of American culture during this period were largely tied to television, movies and commercialism. These cultural and artistic movements all laid the bedrock for Pop Art design.

The Pop Art artists

Although American media and consumerism was the subject of Pop Art, the term originated in the UK in the 1950s. In the European context, Pop Art largely served as a reaction to the encroachment of US pop culture through advertising.

The collages of British artist Peter Blake, for example, often combined US pop culture iconography with those from the UK. His album sleeve for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band famously features a multitude of cultural icons standing prominently behind the Beatles, from Bob Dylan and Fred Astaire to Shirley Temple and William S. Burroughs.

Meanwhile, Pauline Boty, a founder of the British Pop Art movement, regularly incorporated publicity headshots of male and female celebrities into her paintings, combining them with rose petals and vibrant colors in celebratory sensuality.

Later on, her work took on a more critical eye, notably in her 1964 painting It’s A Man’s World I which depicts popular images of famous men as the building blocks to government and warfare.

Across the pond, American artists represented their own relationship with rampant advertising as reflections of both ideals and reality. Similar to how Greek classical artists sculpted their mythic heroes and gods as the epitome of beauty, American media had generated new beauty standards.

Robert Rauschenberg, one of the earliest American Pop Art artists and something of a successor to the “nuts” Dadaist artist Duchamp, created mixed material collages that incorporated discarded objects into paintings, much like the buried artifacts that define lost civilizations. One of his most famous works, a painting titled Retroactive II (1963), utilized commercial silkscreen techniques and appropriation of famous photos, firmly identifying him with the Pop Art movement.

James Gill is another Pop Art artist who featured images of political figures and current events in his art but with a decidedly more critical tone than his contemporaries—The Machines (1965) showing Nixon speaking into microphones whose cables funnel downward into photos of deadly warfare.

Rosalyn Drexler—who boasts pedigree in disciplines ranging from fine art, novel writing and wrestling—similarly constructed her paintings out of disparate collaged images often appropriated from pulp movie posters and painted over them with bold, minimal colors.

Andy Warhol is often recognized as Pop Art’s star, a celebrity ultimately as iconic as those he depicted, and much of his work did come to encapsulate what Pop Art was all about. His famous Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962) was reproduced and displayed in rows and columns—an artistic mirror of supermarket stock. His Marylin Diptych (1962) pioneered Pop Art silk screening to reproduce portraits of the late Marylin Monroe at the height of her fame in vibrant colors, fading to black-and-white and then nothing.

All in all, Pop Art is both a movement associated with Americana but also the artistic counterculture of the 1960s. Nevertheless, its legacy has endured through the ages.

It received a particular revival in the 1980s through Keith Haring, whose energetic humanoids emphasized repetition and commercial reproduction in order to create accessible art. In this way, his murals and pop shop merchandise received massive fame, all while spreading awareness of issues ranging from apartheid to queer discrimination.

In more recent times, artists from Takashi Murakami to Banksy have carried the torch of Pop Art into the modern age.

Pop Art in contemporary design

At the end of the day, Pop Art is a versatile aesthetic that any designer can adapt to their work regardless of which decade they find themselves in. To understand how this is done, let’s take a look at some contemporary designs that channel Pop Art.

Many designers evoke the style through reference and imitation of classic Pop Art works. Not only is this the most straightforward approach, it fits in neatly with Pop Art’s ethos of direct appropriation and parody.

Both Digital Man and oink! design, for example, take this approach to depict logo designs as series of multicolored portraits in homage to Marilyn Diptych, with commercial vector techniques acting as the digital age equivalent of 60s era mass production.

Alebelka and Monsat, meanwhile, use repetition and reproduction to create designs that call to mind Campbell’s Soup Cans.

The above approach works best when the referenced works are well-known, and as a result, it tends to be more evocative of Warhol in particular than Pop Art in general. But in addition to specific works and artists, it is also associated with the 1960s, and aspiring Pop Art artists can choose to hearken back to the aesthetics of this decade. While pop culture has changed drastically over the years, the specific ideals of vintage advertising are still palpable. If anything, the time has only exposed their shallow nature.

Designs in this style showcase (often ironically) 1950s suburban bliss, such as Alice R’s book cover. The vintage illustration of a smiling woman looks like it was ripped directly from an old magazine insert, aside from the stylized color filter. But the accusatory title (translated from French) “So, You’re Still not Married?” makes what would otherwise be an innocent smile look strained.

Vintage superheroes are another recurring element in Pop Art design, particularly for their embodiment of pristine, golden age virtue. Tomie O goes a step further with a packaging design that features not only a superhero but also vintage type and graphic text reminiscent of an old-school shopping catalog.

Besides direct pop culture imagery, many Pop Art artists also incorporated classic techniques of mass production into their work, especially those of halftone dots. These also happen to be reminiscent of polka dots used in the work of famed Pop Art artists like Yayoi Kusama. The great thing about halftones is they can infuse designs with a Pop Art sensibility in a subtle way, making them amenable to any number of design contexts from packaging to logo design.

Make your design pop

Pop Art design is a dynamic, joyful art style that has managed to stick around for half a century, which is not surprising given the powerful impression it conveys.

It appeals to common sensibilities with familiar images and techniques. At the same time, it shows us what we value by reflecting our ads, our idols and even our garbage right back at us. For all these reasons, if you find your designs are too often uninspired, consider for once letting them go pop.

Article Provided By 99 Designs

![]()

If you would like to discuss Your Logo with Mojoe.net or your website’s analytics, custom logo designs, social media, website, web application, need custom programming, or IT consultant, please do not hesitate to call us at 864-859-9848 or you can email us at dwerne@mojoe.net.

Recent Comments